Cilgerran Castle | Visit Amazing Welsh Castles

Cilgerran Castle is next to the River Teifi in west Wales. Built in the early 13th century, it played a key role in defending the contested borderlands between Norman lords and native Welsh rulers.

Its twin-towered gatehouse offers views across the wooded valley below.

The castle’s history reflects the long struggle between the English Crown and the Princes of Deheubarth. Cilgerran still tells the story of medieval power, rebellion, and frontier warfare.

Quick Facts

Date of construction: c. 1108 (Norman origin), rebuilt in stone around 1223

Location: Cilgerran, Pembrokeshire, overlooking the River Teifi

Who built it: Initially established by Gerald of Windsor; later rebuilt by William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke

Key purpose: Military fortress guarding the Teifi Valley; part of Norman efforts to control west Wales

A Brief History

The castle was first built around 1108 by Gerald of Windsor, a Norman baron serving under the Marcher Lords. The original structure was likely made of timber, typical of early motte-and-bailey designs.

In 1165, Rhys ap Gruffydd (The Lord Rhys), ruler of Deheubarth, captured the castle. He held it for much of his reign, using it to strengthen Welsh control in the region. After his death in 1197, the Normans regained ground.

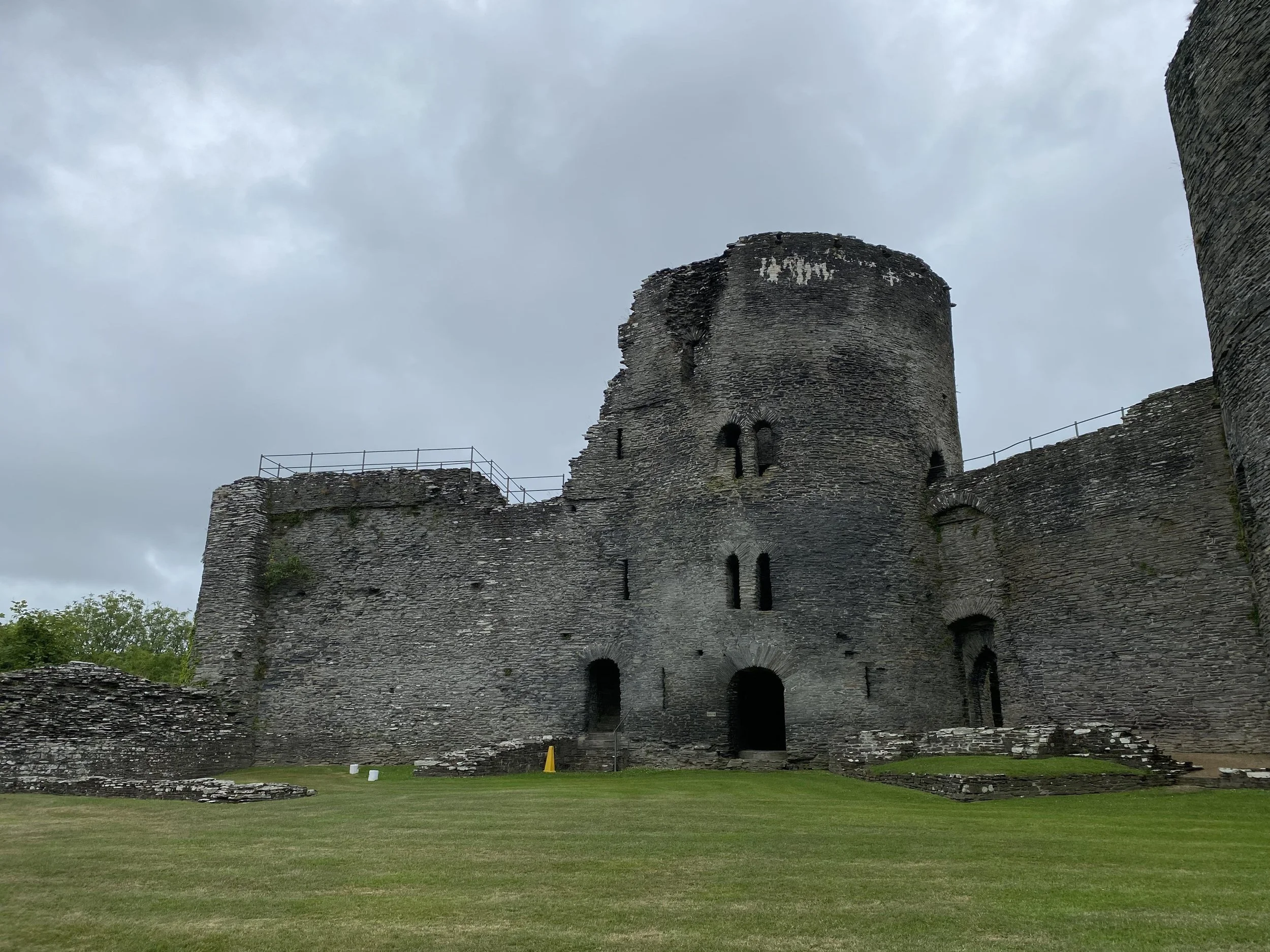

The stone castle you see today began around 1223. William Marshal, one of the most powerful nobles in England, rebuilt it with thick curtain walls and two large round towers flanking the gatehouse. Marshal wanted to secure his estates and project strength in Pembrokeshire.

Cilgerran saw further conflict in the 13th century. Llywelyn the Great attacked it during his campaigns against the English Crown. Despite periods of unrest, the castle remained under Anglo-Norman control.

By the late Middle Ages, Cilgerran lost its military value. It gradually fell into disuse, becoming a romantic ruin by the 18th century. Painters like Turner helped revive interest in the site, and it’s now cared for by Cadw.

Features and Layout

The castle follows a compact design shaped by its natural setting. Built on a rocky outcrop, it uses the steep slopes of the Teifi Gorge as a natural defence on two sides.

The most striking feature is the twin-towered gatehouse. These round towers flank the main entrance and once housed guardrooms and upper chambers. Their design made it easier to defend the gate from above and the sides.

Behind the gatehouse lies a small inner ward, enclosed by thick curtain walls. Inside this space stood domestic buildings, such as a hall, chapel, and kitchens. Only their foundations remain, but you can still trace the outline.

To the west, a second smaller tower stands at the cliff edge. It helped guard the river side, where the slope drops sharply. The curtain walls here are particularly high and narrow, emphasising the limited space available.

A deep rock-cut ditch separates the castle from the higher ground to the east. This man-made defence adds to the site's natural strength, limiting access to a narrow land bridge.

Cilgerran was not a large garrisoned fortress. Instead, its design reflects the need to control a key route and act as a strong local base, rather than a national stronghold.

Images

Legends and Stories

The castle is linked to one of the oldest tales in Welsh legend, the story of Nest ferch Rhys, sometimes called the “Helen of Wales.” Nest was the daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr, the last independent ruler of Deheubarth. After his death, she was taken as a political hostage and later married Gerald of Windsor, the Norman lord who first built the castle.

According to chroniclers, Nest was abducted from Cilgerran by Owain ap Cadwgan, a Welsh prince, around 1109. The event caused a scandal and sparked a cycle of revenge between Norman and Welsh forces. Some say Owain stormed the castle to seize her. Others claim he tricked his way in. Either way, her abduction helped define the bitter conflicts that shaped this region.

In later centuries, the castle’s dramatic setting inspired painters and poets. The artist J.M.W. Turner sketched Cilgerran in the 1790s. His image helped turn it into a romantic symbol of the “wild” Welsh landscape, even as it crumbled into ruin.

Local folklore also speaks of strange lights seen in the gorge below, and sounds of clashing swords on misty mornings, though no specific ghost stories are well documented.

Visiting

Opening Times

The castle is managed by Cadw. It’s open daily from 10:00 to 17:00 (last entry 16:30), from 1 April to 31 October. It’s closed in winter except for pre-booked groups.

Ticket Prices

Adults: £4.80

Children (5–17): £3.40

Family (2 adults + up to 3 children): £16.00

Under 5s: Free

Cadw members: Free

(Prices correct as of 2025, check cadw.gov.wales for the latest info.)

Directions and Transport

Teastle sits above the River Teifi in the village of Cilgerran, about 3 miles east of Cardigan.

By car: Follow signs from the A487 and A478. A small pay-and-display car park is a short walk away.

By public transport: Buses from Cardigan and Newcastle Emlyn stop in Cilgerran village.

Facilities and Accessibility

The site has basic facilities only. There are no toilets on-site, but the village has public amenities nearby. Paths are uneven, with steps and grass underfoot. Wheelchair access is limited due to the terrain and historic layout.

Dog Policy

Dogs are welcome on leads. You’ll need to keep them under control, as the site has sheer drops and livestock nearby.

Nearby Attractions

A visit to the castle fits easily into a wider day out in west Wales. The surrounding area offers river walks, historic sites, and nature reserves.

Teifi Marshes Nature Reserve

Managed by the Wildlife Trust, it’s home to otters, kingfishers, and woodland trails. The Welsh Wildlife Centre has a café, viewing tower, and activities for families.

Cardigan

The town has its own castle, restored in recent years. You’ll also find cafés, galleries, and an independent cinema.

St Dogmaels Abbey

Just north of Cardigan, offers another window into the medieval past. The ruined abbey sits beside a working watermill and a popular local market (Tuesdays).

Cenarth Falls

Known for its natural rock ledges and historic salmon traps. It’s a good spot for photos and picnics.

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park

If you’re planning a longer stay, the coastline offers cliff walks, beaches, and sea views within easy reach.

Visitor Tips

Wear sturdy shoes. The ground is uneven, with steps, grass, and loose stone. Walking boots or trainers are best.

Bring a raincoat, even in summer. The weather in west Wales can change quickly.

Arrive early if you want quiet. Tour groups and walkers tend to arrive mid-morning.

Keep children close, especially near the walls. There are unguarded drops throughout the site.

Allow 45 minutes to 1 hour for your visit. This gives time to explore the ruins and enjoy the views.

Pack snacks or eat in the village. Cilgerran has a few small cafés and a local shop, but no food is sold on site.

Combine your visit with a walk to the Teifi Marshes or a stop in Cardigan for a full day out.

Take binoculars if you’re into wildlife. Red kites and herons often fly over the gorge.

FAQs

-

Yes. Dogs are welcome as long as they’re on a lead. Be cautious near the edges, as there are steep drops.

-

Yes. There’s a small pay-and-display car park nearby. From there, it’s a short walk to the entrance.

-

Most visits take between 45 minutes and one hour. You might stay longer if you explore the nearby nature reserve.

-

The castle is closed during winter, except for pre-booked groups. Check Cadw’s website before travelling.

-

Access is limited. Paths are uneven and there are steps throughout. It’s not suitable for wheelchairs or most buggies.

-

No. The site has no toilets, but public toilets are available in Cilgerran village.

Wrapping it Up

The castle offers a clear view into the history of west Wales. Its clifftop position, twin towers, and rich past make it worth a visit if you're near Cardigan. Though partly ruined, the layout is easy to follow, and the views across the Teifi Valley are striking.

Plan for an hour on site, wear good footwear, and check the weather. With nearby walks, wildlife, and historic spots, Cilgerran fits well into a relaxed day out.

Cardiff Castle is a medieval and Victorian-era site in the centre of Cardiff, the capital of Wales.