Beaumaris Castle | Visit Amazing Welsh Castles

Beaumaris Castle is an unfinished masterpiece of medieval military design, located on the Isle of Anglesey in North Wales. Construction began in 1295 under the orders of King Edward I as part of his campaign to conquer and control Wales.

Though it was never completed, the castle is still considered one of the finest examples of symmetrical concentric design in Britain.

Beaumaris was the last and most ambitious of Edward’s ring of castles in North Wales, designed by the king’s trusted architect, Master James of St George. Its perfectly aligned walls, multiple defensive layers, and commanding sea-facing position show how advanced castle-building had become by the late 13th century.

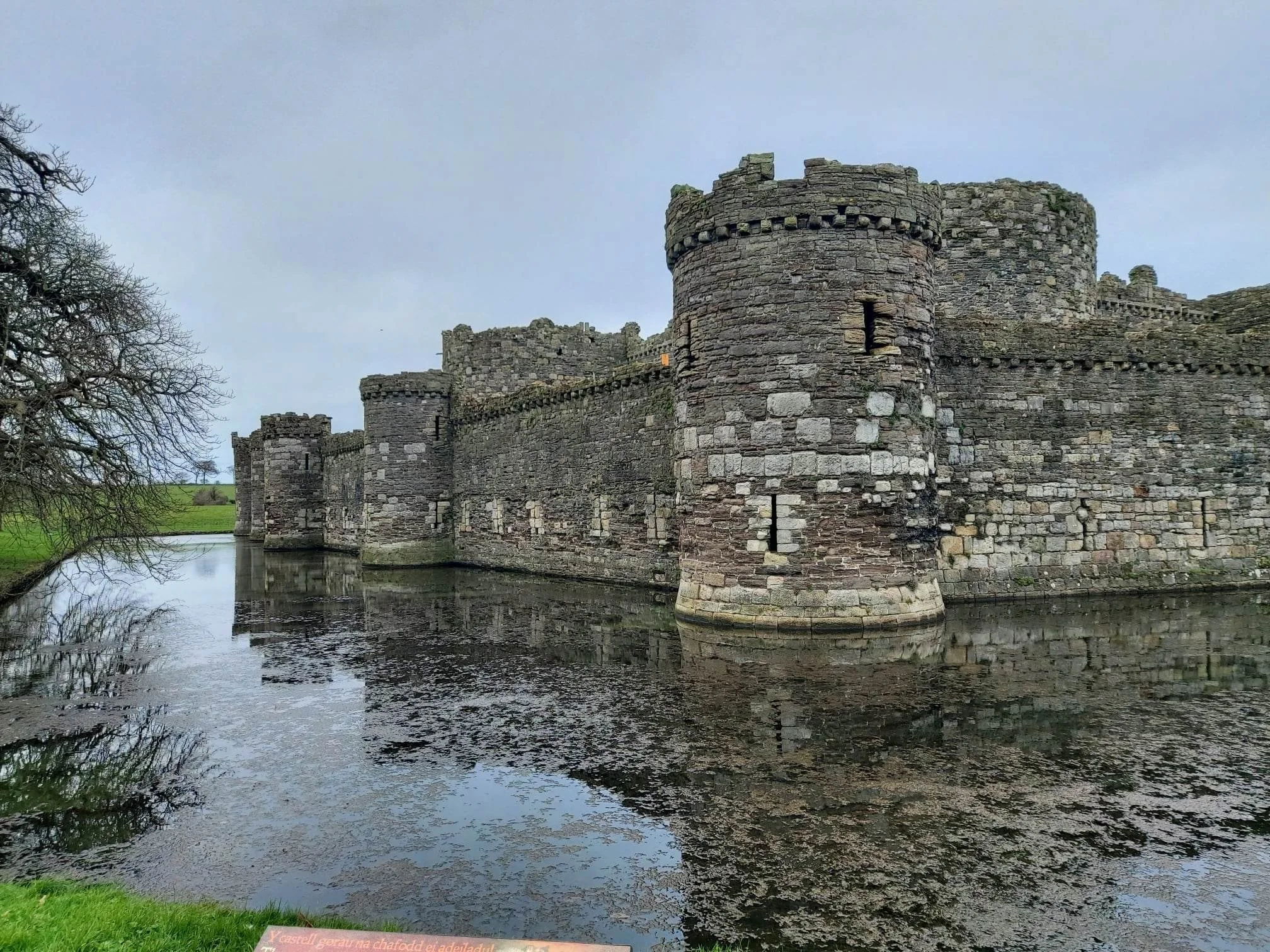

Today, the castle stands as a monument to medieval engineering, with its massive walls, wide moat, and incomplete towers offering a unique insight into both the ambition and limits of royal power.

Quick Facts

Date of Construction: Began in 1295

Location: Beaumaris, Isle of Anglesey, North Wales

Who Built It: Commissioned by King Edward I; designed by Master James of St George

Key Purpose or Historical Use: Military stronghold to secure English control over North Wales

A Brief History

Beaumaris Castle was the final addition to King Edward I’s Iron Ring, a chain of fortresses built to control newly conquered North Wales. Work began in 1295, shortly after a Welsh uprising. Its construction followed Edward’s successful campaigns at Conwy, Caernarfon, and Harlech.

The castle was designed by Master James of St George, an experienced military architect from Savoy. His plans for Beaumaris followed the concentric model: strong outer defences surrounding inner walls and towers. The design offered multiple layers of defence and no blind spots.

Progress was rapid at first, with hundreds of workers and craftsmen on site. However, the project was soon slowed by cost overruns and a lack of funds. By 1330, work had stopped entirely. The castle was never finished, key features like the inner towers and upper walls remained incomplete.

Despite this, Beaumaris remained a functioning garrison and administrative centre for centuries. It saw limited action during the rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in the early 1400s and later during the English Civil War in the 1640s, when it was held briefly by Royalist forces.

From the 17th century onwards, the castle fell into disuse. It became a picturesque ruin, attracting antiquarians and visitors. Restoration efforts in the 20th century helped preserve the remaining structure. Today, it is managed by Cadw and recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Key Features and Layout

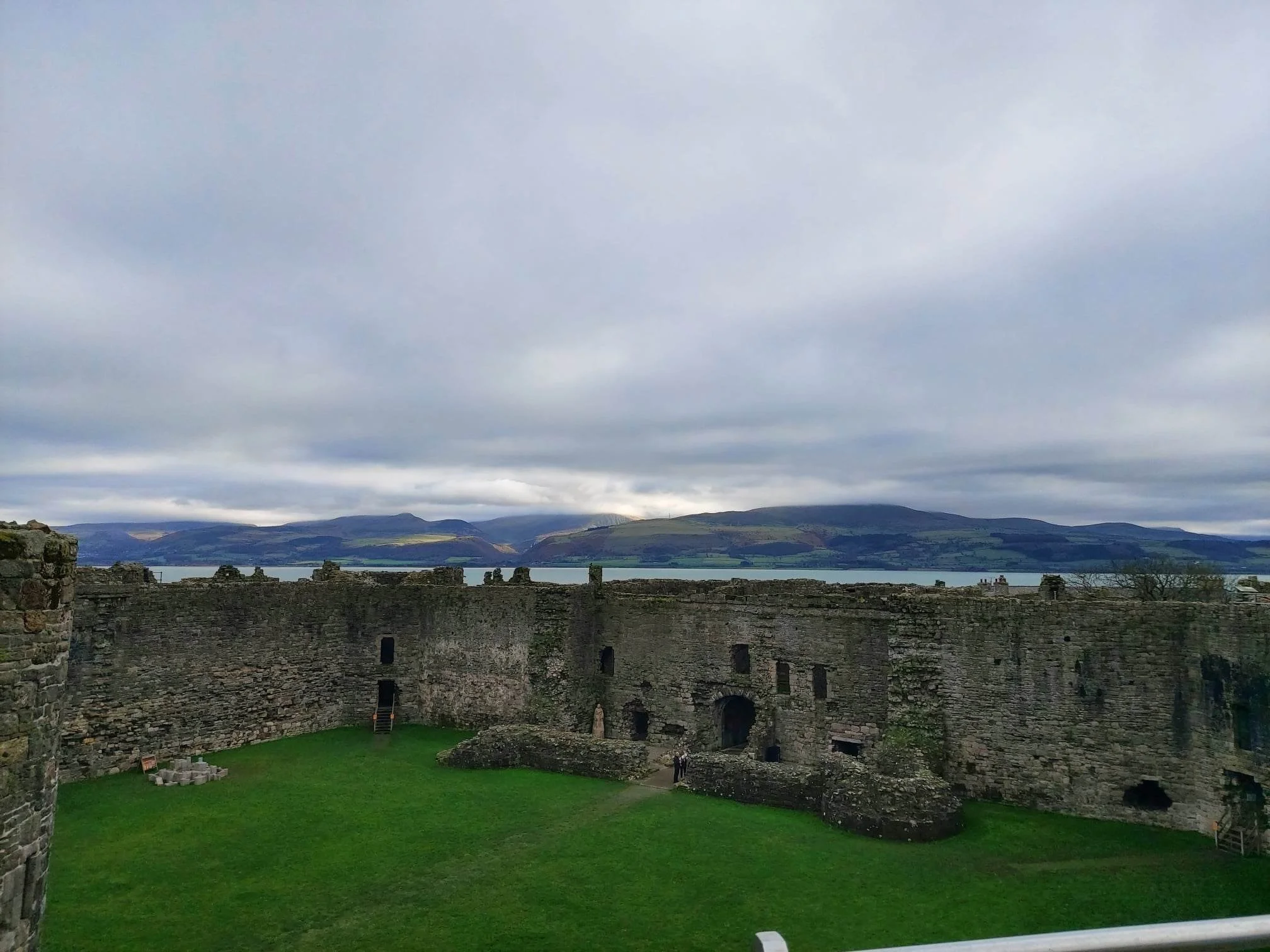

The castle was built to impress as well as to defend. Though unfinished, its structure remains a clear example of concentric design, one line of fortifications inside another. This layout gave defenders a significant advantage, allowing them to fall back to inner walls if outer ones were breached.

The castle has a near-perfect symmetrical layout. A broad moat surrounds the outer curtain wall, which features 16 towers and two main gatehouses. These outer walls were intended to provide overlapping fields of fire in all directions.

Inside the outer wall stands a taller, inner curtain wall, which was designed to include six towers and two more gatehouses. This created four strong defensive layers that attackers would need to break through.

The south gatehouse faces the town and was built as the main entrance. The north gate, which leads to the sea, was designed to allow supplies to be brought in by boat. This was a smart strategic choice, ensuring the castle could be resupplied even under siege.

While the upper floors of the towers and residential chambers were never completed, the ground-floor structures remain. You can walk through large storage rooms, passages, and parts of the barracks. Arrow slits, murder holes, and spiral staircases reveal how carefully the castle was designed for defence.

The sheer scale of the walls and moat show Edward’s ambition, even if the castle was never finished. Beaumaris remains a textbook example of late 13th-century military architecture.

Images

Legends and Stories

The castle is not as well known for ghost tales or mythical stories as some of Wales’s older castles, but it does have a few associations that add to its character.

One of the most common reports from visitors is a sense of eerie silence inside the vast stone walls. Some claim to hear unexplained footsteps echoing in empty corridors, particularly near the south gatehouse. However, these are anecdotal and not linked to any specific legend or named figure.

The castle’s history during the English Civil War has inspired local stories of soldiers who refused to surrender. One tale describes a Royalist officer who stayed behind during the Parliamentarian siege, hiding in the castle’s deeper chambers before eventually escaping by boat under cover of night. While not confirmed by records, this story reflects the castle’s maritime access and layered defences.

Another point of interest lies just outside the castle walls. The name “Beaumaris” comes from Norman-French, beau marais, meaning “fair marsh”, referring to the low-lying site chosen for the build. Local tradition says that villagers from the nearby settlement of Llanfaes were displaced to make way for the new English town. Their forced relocation is sometimes cited as a source of historical unrest in the area.

Though Beaumaris lacks dramatic myths or named ghosts, its quiet presence and unfinished structure often spark the imagination of those who visit.

Visiting

Beaumaris Castle is open to visitors throughout the year and is managed by Cadw, the historic environment service of the Welsh Government.

Opening Times

Summer (1 April – 31 October): 9.30am – 5.00pm daily

Winter (1 November – 31 March): 10.00am – 4.00pm, open most days

Last admission is 30 minutes before closing

Always check Cadw’s official website for up-to-date times: cadw.gov.wales

Ticket Prices

Adults: £8.70

Under 16s / Students / Seniors (65+): £6.10

Family (2 adults + up to 3 children): £28.20

Cadw members: Free entry

Prices may change, so confirm before visiting.

Directions and Transport

Beaumaris is located on the eastern side of Anglesey. It’s around 6 miles from Menai Bridge and 9 miles from Bangor.

By Car: Use postcode LL58 8AP for sat nav. There’s a pay-and-display car park next to the castle.

By Bus: Regular buses run from Bangor and Menai Bridge to Beaumaris.

By Foot: The town is walkable, and the castle is in the centre, near the waterfront.

Facilities and Accessibility

Accessible toilets are available on site.

Parts of the castle have uneven ground and steps. Some areas are not suitable for wheelchairs or prams.

There is a visitor information board and staff available to help with access needs.

Dog Policy

Dogs are allowed on leads in the castle grounds.

Only assistance dogs are permitted inside any enclosed exhibition areas (if in use).

Nearby Attractions

The castle is well placed for a full day out on Anglesey, with plenty to see and do nearby.

Beaumaris Town

The town itself is worth exploring. It has a mix of Georgian architecture, independent shops, cafés, and pubs. You’ll also find a Victorian pier, offering views across the Menai Strait to the mountains of Snowdonia.

Beaumaris Gaol

Just a short walk from the castle, this 19th-century prison is now a museum. It offers a stark contrast to the grandeur of the castle and gives insight into Victorian justice. You can explore original cells, the treadwheel, and even a recreated execution room.

Penmon Priory and Trwyn Du Lighthouse

A few miles to the east of Beaumaris, Penmon Priory is a peaceful site with ancient stonework and a holy well. From there, a short drive or walk brings you to Trwyn Du Lighthouse. It’s a striking spot, especially at sunrise or sunset.

Puffin Island

Visible from the castle’s sea gate, Puffin Island is home to seabirds and seals. While you can’t land on the island, boat trips run from Beaumaris Pier, offering views of the island and the surrounding coast.

Walks and Views

The Anglesey Coastal Path passes through Beaumaris. You can follow it for scenic walks along the Menai Strait or inland to wooded trails. Views of Snowdonia across the water are especially clear on bright days.

Visitor Tips

To make the most of your visit to Beaumaris Castle, a bit of preparation goes a long way.

What to Bring

Wear sturdy shoes. The stone floors and steps can be uneven, especially in wet weather.

Bring a raincoat or windproof jacket. Even in summer, the coastal location can be breezy.

If you're taking the bus or walking, carry water and snacks, as options inside the site are limited.

Best Times to Visit

Mornings are generally quieter, especially on weekdays.

If possible, avoid school holidays and summer weekends for a more peaceful visit.

Spring and early autumn offer the best balance of good weather and smaller crowds.

Exploring the Site

Allow at least 1–1.5 hours to walk the full perimeter and explore the towers and inner courtyard.

Information boards are dotted throughout and give useful historical context.

Parts of the castle are roofless, so check the forecast before your trip.

Families and Dogs

Children can explore freely, but supervision is needed on higher walkways and stairs.

The site is dog-friendly, as long as dogs are kept on a lead.

Bring waste bags, as bins are limited.

FAQs

-

Yes, dogs on leads are welcome throughout the castle grounds. Only assistance dogs are allowed in any enclosed or exhibition areas, if open.

-

Some areas of the outer grounds are accessible, but most of the inner castle includes stairs, uneven stonework, and narrow passages. Wheelchair access is limited.

-

Most visitors spend between 1 and 1.5 hours exploring the site. You may want more time if you're interested in the details of the architecture or combining your visit with nearby attractions.

-

Yes, there is a pay-and-display car park directly next to the castle entrance. Additional parking is available in the town.

-

You can access some tower sections, but not all. The upper levels were never completed, and access may be restricted for safety.

-

Yes. It’s a Cadw site, and members get free entry. Joint Cadw–English Heritage members are also eligible.

Wrapping it Up

Beaumaris Castle offers a striking look at medieval military design, even in its unfinished state. Its concentric walls, sea access, and strategic location reflect the ambition of Edward I’s campaign in Wales. Though it never saw major battles, the castle played a steady role in English control of the region and later became a symbol of historic authority on Anglesey.

If you're exploring North Wales, especially the Isle of Anglesey, the castle is worth adding to your itinerary. It's close to other attractions, easy to reach, and offers clear insight into the power structures of the medieval period. Just bring good shoes and perhaps a camera for those views across the Menai Strait.

The castle was built on the site of a medieval fortified manor, the current structure was designed by architect Thomas Hopper for the wealthy Pennant family.