Caergwrle Castle | Visit Amazing Welsh Castles

Caergwrle Castle is a ruined medieval fortress in Flintshire, North Wales. It was built in the late 13th century during the reign of Edward I, a period marked by intense military activity across the Welsh borderlands.

The castle stands on a rocky hill above the village of Caergwrle, offering commanding views across the Alyn Valley and towards the Cheshire Plain.

It is notable for being the only stone castle constructed by a native Welsh prince during Edward I’s campaigns. Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd, brother of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, began building Caergwrle in 1277 after siding with the English crown. The castle’s history is short but significant. It reflects the shifting alliances and power struggles of the time.

Quick Facts

Date of construction: 1277

Location: Caergwrle, Flintshire, North Wales

Who built it: Dafydd ap Gruffudd, Prince of Gwynedd, under the overlordship of King Edward I

Key purpose or historical use: Built as a defensive stronghold and symbol of alliance between Dafydd and the English crown. It was later involved in the final rebellion of the Welsh princes.

A Brief History

Dafydd ap Gruffudd began building in 1277. This followed his defection to King Edward I during the English invasion of Wales. As a reward, Edward granted him lands in northeast Wales and permission to build a castle.

Construction began immediately. The site had likely been occupied before, possibly by an Iron Age hillfort. Dafydd started work on a stone fortress, a rare privilege for a Welsh prince. However, in 1282, Dafydd turned against Edward and launched a rebellion. Caergwrle became part of that conflict.

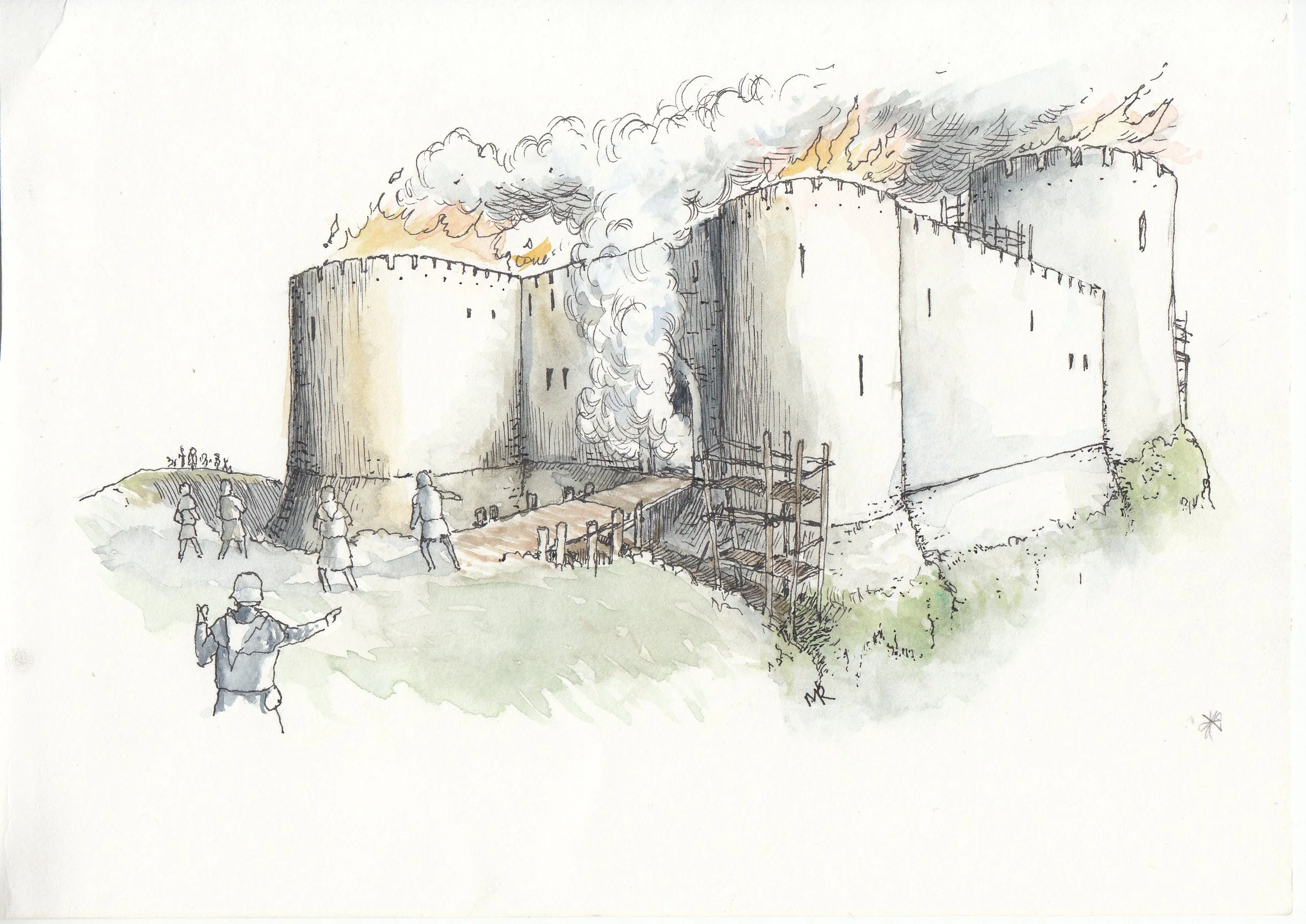

Edward’s forces quickly seized the castle. The English garrison took control, but in 1283, a fire severely damaged the structure. The cause of the fire is uncertain, but it made the castle uninhabitable.

Edward ordered repairs, and materials were brought in, including timber and lead from Cheshire. Despite this, rebuilding efforts stalled. By 1284, Edward granted the damaged site to Queen Eleanor of Castile. There’s no evidence she restored it. The castle was abandoned soon after.

By the 14th century, Caergwrle had already fallen into ruin. Today, its remains tell the story of a short-lived but important fortress tied closely to the end of Welsh independence.

Layout and Features

The Castle was built on a steep, rocky hill that provided natural defence on all sides. The stonework you see today shows a compact, irregular design. This followed the shape of the hill rather than a strict geometric plan.

The castle had two main wards. The inner ward was the stronghold. It included living quarters, a water cistern, and a small keep or tower on the highest point. This upper area gave defenders clear views over the Alyn Valley.

The outer ward sat slightly lower, possibly containing service buildings or stables. A curtain wall ran around the entire structure, with towers built into it for added defence.

A deep ditch cut into the rock guarded the main approach. A gatehouse once controlled access into the site. Though it is now ruinous, foundations suggest a secure entrance with defensive features like portcullises and drawbridges.

Stone from local quarries made up the main building material. Much of the surviving walling is rough-hewn, and some areas still show signs of fire damage from 1283.

Because the castle was never fully rebuilt, it remains a raw example of late Welsh construction with minimal English modification.

Images

Legends and Stories

Local folklore ties the site to an earlier hillfort, and speak of a well beneath the hill once used for healing rites before the medieval building stood.

A ghost story centres on Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd. Some say his spirit haunts the castle grounds, guiding lost visitors under the moonlight.

A more spooky story tells of a “Dark Lady” seen drifting through the ruins. Witnesses describe a pale figure, her feet hovering centimetres above the earth, gliding silently beneath the battlements.

Close by, on the 17th-century Packhorse Bridge, villagers speak of Squire Yonge’s ghost. One account recalls:

“The ghost of ‘Squire Yonge’ walks to and fro… snapped during a night watch on the historical Packhorse Bridge”

These legends reflect the castle’s layered history, from Iron Age rites to medieval dramas and local superstition.

Visiting

Opening times & ticket prices

Caergwrle Castle is open all year, during daylight hours. It is free to enter, as part of Cadw’s guardianship scheme. It closes only on 24–26 December and 1 January.

Directions and transport

The castle sits above Caergwrle village, along a waymarked path from the junction of Wrexham Road and Castle Street. You can reach Caergwrle by train via the Borderlands Line from Wrexham Central or Shotton; the station lies about a 10-minute walk uphill to the castle. Alternatively, drive along the A541, and park in village car parks off High Street.

Facilities and accessibility

Car parking: Public parking is available in the village centre .

Terrain: The route is moderately challenging, with an uneven, steep ascent .

Dogs: Well-behaved dogs on short leads are welcome on the ground-floor area.

Facilities: No visitor centre, toilets, or refreshment outlet on site. Interpretation boards provide basic context.

Accessibility: The uneven paths and incline make the site unsuitable for wheelchairs or small children without good mobility.

Nearby Attractions

Hope Mountain

Just west of the castle lies Hope Mountain. It offers panoramic views of the Clwydian Range and Merseyside. Several marked trails suit walkers of all levels.

Packhorse Bridge

The 17th-century Packhorse Bridge in Caergwrle is a short walk from the castle. It crosses the River Alyn and features in local ghost stories.

Wrexham

The market town of Wrexham is about 7 miles south. Highlights include St Giles’ Church, Ty Pawb arts centre, and Erddig Hall, a National Trust site with gardens and a preserved historic house.

Castell Dinas Brân

For more medieval exploration, Castell Dinas Brân near Llangollen offers a spectacular hilltop ruin with views across the Dee Valley.

Offa’s Dyke Path

The national trail passes nearby. Walkers can connect to sections from Hope, offering scenic routes along the historic earthwork boundary.

Visitor Tips

Footwear: Wear sturdy shoes. The path to the castle is steep, with uneven ground and loose stones.

Weather: Bring waterproofs if rain is forecast. The site is exposed, and there’s no shelter.

Best time to visit: Weekday mornings offer the quietest experience. In summer, visit early or late in the day to avoid heat and glare.

Bring water and snacks: There are no facilities at the site. The nearest cafés and shops are in Caergwrle village.

Photography: Light is best from midday to late afternoon. The views east across Cheshire are excellent.

Family visits: Children will enjoy exploring, but supervision is needed due to drops and unstable areas.

Accessibility: Not suitable for wheelchairs or pushchairs. The final approach is unpaved and narrow.

FAQs

-

Yes. Dogs are welcome if kept on a short lead. The site is open access but has steep paths and unfenced drops.

-

No. Caergwrle Castle is free to visit and open all year during daylight hours.

-

Yes, with care. The site has uneven ground, steep climbs, and no barriers along edges. Children should be supervised.

-

Yes. Public car parks are available in Caergwrle village. The walk to the castle takes about 10–15 minutes uphill.

-

No. The castle is reached via steep, unpaved paths. The terrain is unsuitable for wheelchair users or those with limited mobility.

-

No. There are no facilities on site. Shops and cafés are available nearby in the village.

-

Allow around 30–60 minutes to explore the castle and read the interpretation boards. Longer if combining with local walks.

Wrapping it Up

Caergwrle Castle offers a quiet, rewarding visit for those interested in medieval Welsh history. Though ruined, its layout and setting still reveal much about its short life under Prince Dafydd ap Gruffudd and Edward I.

The site suits independent travellers who enjoy walking and exploring at their own pace. You won’t find cafés or ticket booths here, just history, landscape, and a strong sense of place.

If you're visiting North Wales or the Welsh Marches, Caergwrle makes a useful stop, especially when paired with nearby walks or historical sites. Bring good footwear, check the weather, and enjoy the views.

Cardiff Castle is a medieval and Victorian-era site in the centre of Cardiff, the capital of Wales.